India’s National Geospatial Digital Public Infrastructure (Geo‑DPI): The Next Big Leap

India’s governance architecture is evolving rapidly, and at the heart of this transformation is spatial intelligence. The National Geospatial Digital Public Infrastructure, or Geo‑DPI, represents a seminal shift in how the government integrates, standardizes, and uses geospatial data at scale. Building on the foundation laid by digital public infrastructure platforms such as Aadhaar and UPI, Geo‑DPI aims to serve as the underlying spatial framework that supports policy design, implementation, monitoring, and cross‑sector coordination across the nation. This initiative, anchored in the National Geospatial Policy 2022, positions geospatial data and services as strategic national assets that can strengthen governance, improve citizen services, enhance infrastructure planning, and support economic growth.

Geo‑DPI Vision: Building a Unified National Geospatial Framework

The vision of Geo‑DPI is rooted in the goal of establishing a unified national geospatial infrastructure that eliminates data silos, improves interoperability between government systems, and delivers a shared spatial reference across programmes at the central, state, and local levels. Under the National Geospatial Policy 2022, geospatial information is formalized as a key enabler of evidence‑based governance, supporting inclusive development, smart planning, and resource optimization through spatial analytics. The policy emphasizes open standards, interoperability, and liberalized access to spatial data, enabling government agencies, Indian enterprises, and research institutions to generate and harness geospatial insights at scale.

This vision is also aligned with broader national objectives such as Viksit Bharat 2047 and the Digital India agenda, which call for strengthened digital infrastructure, improved public services, and enhanced economic competitiveness through technology integration. Through Geo‑DPI, spatial intelligence becomes both a governance tool and a public good driving better outcomes for citizens.

Core Components: One Nation, One Map and Beyond

At its core, Geo‑DPI consists of several foundational components that work together to create a cohesive spatial ecosystem. The One Nation, One Map (ONOM) framework is the central pillar, ensuring that all spatial data references a common, authoritative base map.

This eliminates inconsistencies that arise when different ministries or agencies use divergent spatial references for planning, mapping, or monitoring functions.

Standardized geospatial base maps cover administrative boundaries, transportation networks, hydrography, topography, urban and rural settlements, environmental features, and other critical layers. Interoperable APIs (Application Programming Interfaces) serve as the conduits through which data can be securely shared and consumed by various government systems, private sector platforms, researchers, and developers.

National geospatial registries catalog authoritative datasets with metadata, quality indicators, and usage conditions that support transparency and reusability. These registries act as national catalogues of spatial information, facilitating standardization while reducing redundant data creation efforts across ministries and state governments.

Supporting these components are governance protocols and frameworks that ensure data quality, compliance with standards, and secure access. Federated data governance mechanisms help manage sensitive information while enabling broad cross‑sectoral utilization of spatial datasets.

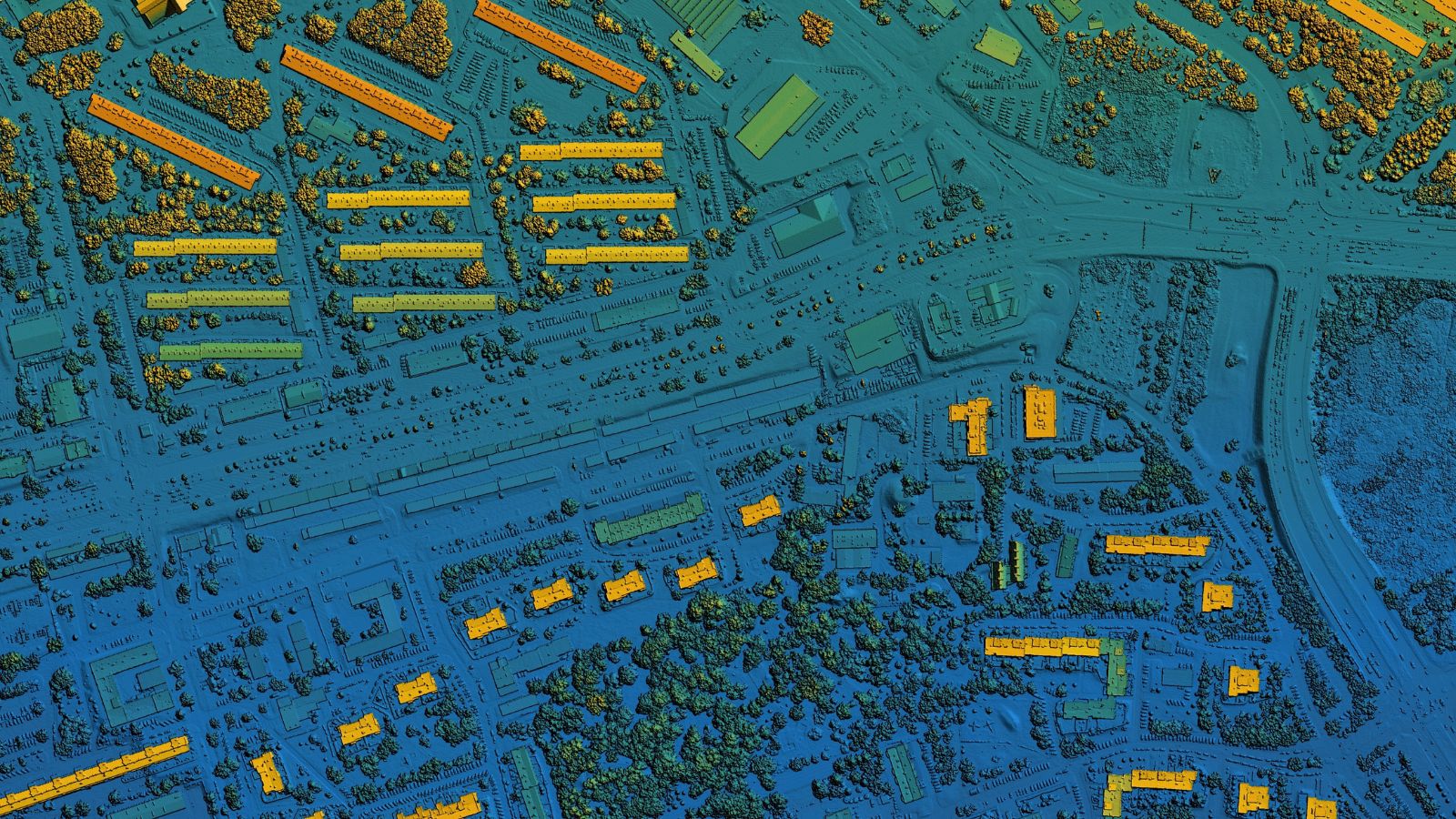

Technology Stack: Survey of India Maps, Cloud GIS, and AI‑Driven Data Validation

Geo‑DPI’s technology backbone blends legacy and modern capabilities to provide a robust, scalable, and real‑time infrastructure. Survey of India (SoI) maps serve as the authoritative spatial reference, providing baseline geodetic and topographic information that underpins all national spatial datasets. The integration of SoI data with a cloud‑native GIS (Geographic Information System) infrastructure enables storage, processing, and delivery of large volumes of spatial data efficiently and at scale.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning play a central role in data validation, quality assurance, and anomaly detection, helping automate the cleansing and harmonization of multi‑source spatial inputs from satellites, drones, ground surveys, and IoT sensors. The launch of the National Geo‑Spatial Platform (NGP) in late 2025 marked a key milestone in this evolution, offering a centralized hub for authoritative datasets available through modern web services, API interfaces, and analytical tools. This platform is designed to support evidence‑based planning across agriculture, infrastructure, logistics, urban development, environmental monitoring, and other domains.

Continuously Operating Reference Stations (CORS) are another critical technological component, established across the country to support centimeter‑level positioning accuracy. As of 2025, more than 1,100 CORS stations have been deployed, enabling high‑precision positioning for surveying, precision agriculture, construction, and infrastructure projects. With over 14,600 registered users consuming millions of data hours, India’s geospatial network is demonstrating strong adoption across sectors.

Use Cases: Cross‑Ministry Projects and Real‑World Impact

Geo‑DPI is already being used in multiple national programmes that cut across ministries and sectors, exemplifying how spatial intelligence can improve planning, execution, and oversight.

Under the PM Gati Shakti National Master Plan, geospatial data from over 1,600 spatial layers has been integrated into a unified planning interface, enabling ministries such as Road Transport and Highways, Railways, Ports, and Energy to coordinate infrastructure planning with land use, environmental, and settlement data. This integration helps resolve conflicts early, optimize alignments, and prevent cost overruns, thereby reducing project timelines and improving outcomes.

The NAKSHA programme (National Geospatial Knowledge‑based Land Survey of Urban Habitations) has made significant progress in modernising urban land records. Pilots covering 157 urban local bodies across 27 states and 3 union territories have created high‑accuracy, GIS‑linked urban land databases through GNSS surveys, drones, and Web‑GIS platforms. This transition from paper‑based records to digital systems has enhanced transparency, improved property rights accuracy, and supported municipal governance across jurisdictions.

In water governance, spatial intelligence has enabled effective monitoring of rural water supply infrastructure under the Jal Jeevan Mission, allowing administrators to identify underserved areas and prioritize investments. Geospatial tracking and visualisation of pipeline networks, sources, and service coverage have made real‑time monitoring possible, strengthening equitable water service delivery.

The use of spatial analytics extends to agriculture and disaster management as well. Precision agriculture applications leverage CORS positioning and AI‑enriched satellite data to support crop mapping, irrigation efficiency, and soil condition monitoring, contributing to improved resource optimization and farmer advisories. In disaster risk reduction, geospatial dashboards that integrate hazard layers with demographic and infrastructure

data help authorities plan evacuations, allocate resources, and coordinate emergency response with speed and accuracy.

Challenges and Opportunities

While Geo‑DPI has delivered measurable value, there remain challenges that warrant sustained attention. Ensuring data quality and consistency across ministries, states, and local bodies is critical to maintaining the reliability of spatial analytics. The need for continuous updates, real‑time integration, and sensor data ingestion requires robust technical infrastructure and governance mechanisms.

Capacity building is an operational priority as well. Government departments, urban local bodies, and state agencies require ongoing training in geospatial analysis, data interpretation, and platform use to translate spatial data into actionable insights.

At the same time, Geo‑DPI presents significant opportunities for innovation. Public‑private collaboration can accelerate the development of domain‑specific applications, while AI and machine learning unlock predictive modelling capabilities that enhance resilience and planning. Strengthening data governance frameworks and expanding federated access models will further empower startups, researchers, and private sector innovators to build solutions on top of Geo‑DPI.

Conclusion

India’s National Geospatial Digital Public Infrastructure represents a strategic convergence of technology, policy, and governance. By standardising spatial data, enabling interoperable systems, and harnessing advanced analytics, Geo‑DPI is enhancing the effectiveness of national programmes, improving transparency, and driving evidence‑based decision‑making. As the ecosystem matures in 2026 and beyond, Geo‑DPI will continue to be a foundational infrastructure for inclusive growth, sustainable development, and responsive governance, positioning India as a global leader in spatially enabled public systems.

Leave a Comment